Most Americans have at least a passing awareness that the United States controls a slice of land in Cuba called Guantanamo Bay, aka "Gitmo." And, I'm sorry if you can't handle this truth, but I bet most of your Gitmo knowledge came from watching the 1992 Tom Cruise/Jack Nicholson/Demi Moore film, "A Few Good Men."

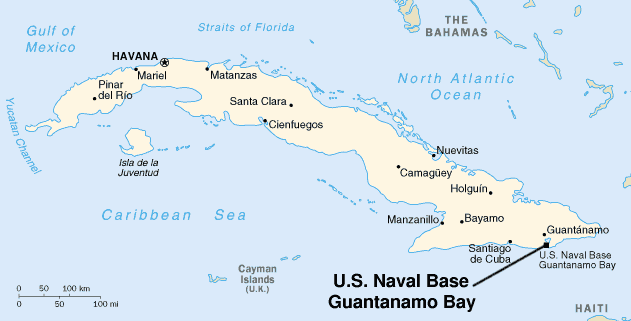

I'll admit something that I bet is true for many people – For a long time, I thought Guantanamo Bay was an island. Perhaps a little tiny circle of rock just off Cuba's coast that the Navy commandeered a hundred years ago, and never gave back. That's not quite the case.

Guantanamo Bay Naval Base is actually a 46.8-square-mile patch of land and water on the far eastern edge of mainland Cuba. To put that in perspective, it's about the same size as San Francisco.

Let that sink in: Imagine if the U.S. owned a San Francisco-sized area INSIDE of North Korea. And not only did we own it, imagine if we parked thousands of American troops, armored vehicles, aircraft, and weapons there, and kept them on permanent alert.

As bizarre as that scenario sounds, it's exactly what's been going on in Cuba for over a century.

So, how, exactly, did the United States end up with a military base in communist Cuba?

The History of Guantanamo Bay

Guantanamo Bay's recorded history stretches back centuries, long before there was a United States. In 1494, during his second voyage to the New World, Christopher Columbus anchored in the bay while on an ultimately fruitless hunt for gold.

Its deep, protected harbor made it a prized stopover in the centuries that followed, first for pirates, then later for the British Navy.

Fast forward to 1898 and the Spanish-American War: a conflict largely driven by U.S. intervention in Cuba's fight for independence from Spain. During the war, a battalion of 647 U.S. Marines landed at Guantanamo Bay and managed to defeat a force of 7,000 Spanish troops—a stunning mismatch made possible by superior firepower and naval support. The U.S. quickly realized the strategic value of the harbor and took control of the surrounding land and waters.

That control was formalized a few years later, in the 1902 Cuban-American Treaty. The newly independent Cuban government agreed to lease Guantanamo Bay to the United States for use as a naval base.

Rental Agreement

Following the Spanish-American War, the U.S. formalized its presence in Guantanamo through a series of agreements with Cuba's newly independent government. In 1903, President Theodore Roosevelt signed a lease granting the United States use of the bay as a "coaling and naval station."

A key element of the treaty was giving the United States "complete jurisdiction and control over and within said areas." The only restrictions the Cuban government put on the United States in regards to Guantanamo Bay were that the area be used only as a coaling and naval station, and vessels engaged in trade with Cuba would retain free passage through the bay encompassed by the site.

A second agreement was signed by President Roosevelt on October 2, 1903, that expanded on the initial lease. According to the terms that were laid out in this agreement, the United States would pay Cuba a rental fee of $2,000 per year, paid in gold. Another stipulation was that all fugitives from Cuban justice who were fleeing to the U.S. Naval base would be returned to Cuban authorities.

Then came the 1934 Treaty of Relations, which reaffirmed the lease and made it effectively permanent: it could only be terminated by mutual consent or if the U.S. voluntarily left.

As you might have guessed, Fidel Castro was not a fan of the rental agreement that he inherited. After coming to power in 1959, Castro refused to recognize the treaty and denounced it as a relic of U.S. imperialism. The failed Bay of Pigs invasion in 1961, in which the CIA tried to overthrow his government, only cemented his hostility toward the American military footprint on Cuban soil.

To this day, the Cuban government maintains that the U.S. "illegally usurped" the land under a coercive and outdated agreement.

Aerial view of GITMO in 1988 (via Getty)

So, how does Cuba protest?

When Fidel came into power, his government stopped cashing our rent checks! Actually, that's not totally true. Cuba did cash ONE of our checks back in 1959, but it was a clerical error by an accountant who didn't know any better.

Cuba hasn't cashed any of the checks we've sent every month over the last several decades, even after we voluntarily increased our own rent to $4,085 per year.

The checks are sent every month straight from the United States Treasury. They are made to the "order of Tesorero General De La Republica De Cuba" (order of Treasurer General of the Republic of Cuba):

GTMO: WWII To The Present

During World War II, Gitmo was used as a base for naval postal operations. The base was also an important distribution point for shipping convoys from New York City and Key West to the Panama Canal, Puerto Rico, Jamaica, and Trinidad and Tobago.

From the end of World War II through the mid-1990s, Gitmo was used as a Fleet Training Facility for Navy units. The stable acoustic conditions for echo ranging made the sea close to Guantanamo Bay perfect for training the crew of Naval vessels in anti-submarine warfare, and deploying convoys to the Southern Atlantic. Additionally, the Bay and its adjacent islands provided excellent amphibious training. This led to the 1st Marine Division at Guantanamo Bay.

Fleet Training Group activities ended, and those troops left Cuba in 1995. At this point, the base's nearly 100 years of usefulness to the U.S. Navy came to an abrupt end. The Navy shifted Gitmo into Minimum Pillar Performance (MPP), which basically meant the base was in a caretaker status, with only the barest of resources to maintain the provisions of the 1934 treaty.

As we all know, the September 11th attacks brought a whole new purpose to GITMO. As American forces rounded up "high-value detainees", military leaders realized that a large area was needed to hold everyone. The contenders for this area were Guam, Diego Garcia, Wake Island, and Guantanamo Bay.

Ironically, the problem with the first three areas is that they all have legal treaties with foreign states that would have provided the prisoners' basic rights. Both Guam and Wake Island are pretty much American islands. If you want to get technical, they are "unincorporated territories of the United States, administered by the Office of Insular Affairs and the U.S. Department of the Interior".

Diego Garcia is a tiny footprint-shaped coral atoll that is administered by the British Indian Ocean Territory. So, prisoners housed on these three islands would technically have the same rights afforded to a citizen of the US or Britain.

Even more ironically, because GITMO was not US soil and the US did not have any sort of treaty with CUBA, the legal status of prisoners was very murky. Theoretically, prisoners living on GITMO wouldn't have the same rights under American laws (most notably the right to legal representation, rights of prisoners, and rights to the American legal system). In fact, a US government official actually referred to the base as the "legal equivalent of outer space."

On January 4, 2002, U.S. Southern Command took custody of designated detainees for further disposition at Guantanamo Bay. The base was used to secure captured enemy combatants from the war on terrorism and to set up and operate a holding facility for al-Qaeda, Taliban, and other terrorists. The War on Terrorism, of course, led the U.S. military to start an interrogation effort on the detainees in support of Operation Enduring Freedom.

In January 2009, President Obama signed executive orders directing the CIA to shut what remains of its network of secret prisons and ordering the closing of the Guantanamo detention camp within a year. But that didn't happen.

On January 20, 2015, Barack Obama said the following during his State of the Union address:

"As Americans, we have a profound commitment to justice — so it makes no sense to spend three million dollars per prisoner to keep open a prison that the world condemns and terrorists use to recruit. Since I've been President, we've worked responsibly to cut the population of GTMO in half. Now it's time to finish the job. And I will not relent in my determination to shut it down. It's not who we are."

Fidel Castro died a year later with no change in GITMO's status.

In February 2021, President Joe Biden announced the launch of a formal review of America's military prison at Guantanamo.

As of mid-2025, just 12 detainees remain held under post-9/11 counterterrorism authorities, most at Camp 6, a high-security facility inside the complex.

But Gitmo's role has quietly expanded again—this time as a controversial outpost in America's immigration crackdown.

In early 2025, the Trump administration began transferring foreign nationals from Africa, Asia, Europe, and Latin America to immigration detention facilities at Guantanamo Bay. Internal government records revealed that detainees included citizens of China, Liberia, Jamaica, the United Kingdom, Venezuela, and Nicaragua. The administration claims many of them are "high-risk," with criminal records or alleged gang ties. But reporting has shown that "low-risk" detainees—individuals with no criminal history at all—have also been sent to the base, often housed in the Migrant Operations Center, a barracks-style facility traditionally used for asylum seekers intercepted at sea.

Others, including those labeled high-risk, are being held at Camp 6—just yards away from the remaining terrorism suspects.

As of July 1, 2025, there were 54 immigration detainees at Guantanamo Bay: 41 in Camp 6 and 13 in the Migrant Operations Center. The administration has spent more than $21 million on flights alone to transfer detainees to the base.

Critics, including civil rights groups and members of Congress, have called the move unconstitutional and inhumane. They argue that housing immigration detainees on Cuban soil strips them of access to due process and legal counsel. The White House has largely refused to release details about who is being detained and why, though Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem and Trump adviser Stephen Miller have publicly praised the expansion.

In recent months, the administration has even floated the idea of building new domestic detention centers, including one in the Florida Everglades dubbed "Alligator Alcatraz."

So far, Guantanamo Bay remains one of the strangest, most legally controversial chapters in modern U.S. history—and it continues to evolve in ways few could have predicted when the lease was first signed over a century ago.

Bengali (BD) ·

Bengali (BD) ·  English (US) ·

English (US) ·